An implementation of transformer-based patched time-series forecasting, inspired by TimesFM

This post is meant to serve as an implementation guide and an example of transformer-based time series prediction with PyTorch, strongly inspired by the recent Google model TimesFM. It is not meant as an introduction the either time-series forecasting or transformers but rather purely to their combination and consequently we expect the reader to have some degree of familiarity with the basic transformer architecture. The text contains several code snippets which illustrate the main components and the goal is for the reader to be able to adapt the full implementation to their own data after reading.

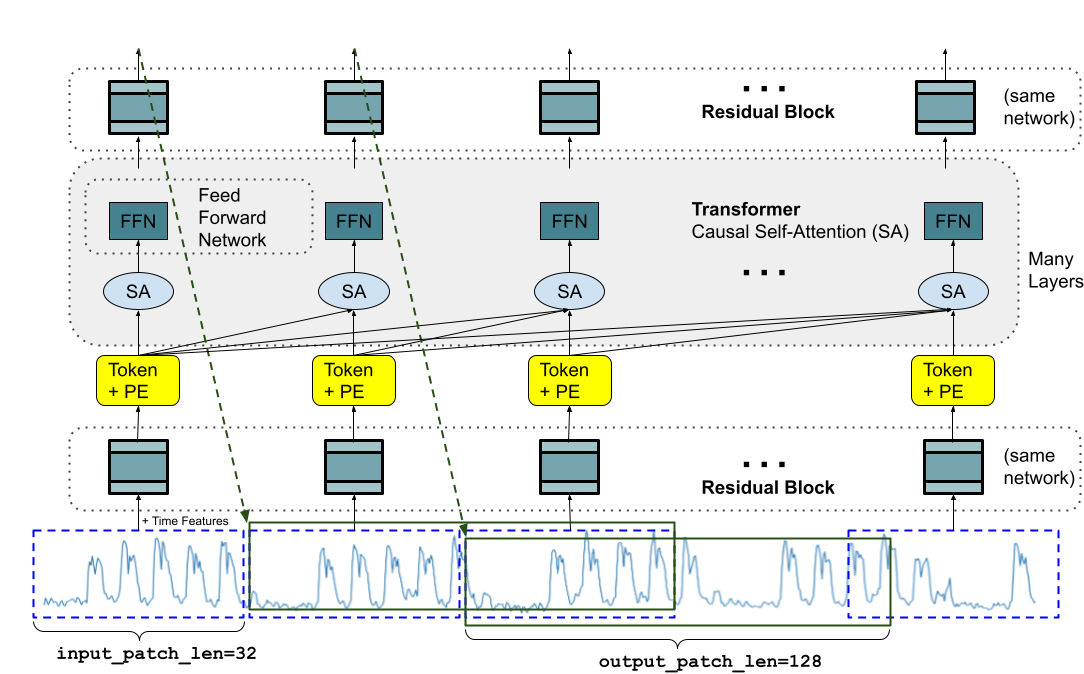

TimesFM is a foundation model for time series prediction which has been trained on a large corpus of data which can be fine-tuned for specific applications. On a high level, the TimesFM model is rather vanilla and consists of an encoder which converts the input time series to a sequence of tokens, a standard decoder-only transformer implementation and a decoder which maps to the prediction vector. Our implementation will be smaller and not support variable input length but should be usable as a starting point for additional features such as support for multivariate time series, conditioning on external variables and probabilistic output data.

Over the last 5 years, the field of time-series prediction has gone through something of a revolution with machine learning methods generally dominating the various leaderboards instead of statistical or hybrid models. Apart from TimesFM, foundation models such as Chronos by Amazon, TimeGPT by Nixtla and PatchTST by IBM all use transformer backbones and achieve excellent results. There are also prominent non-foundation and non-transformer based methods such as N-BEATS and Autoformer with comparable results.

As will hopefully become clear throughout the text, the fact that the encoder and decoder are decoupled from the main model means that large parts of the model can be reused for other purposes. Consider e.g. an encoding procedure which takes in a time-frequency representation of historical data and a decoder which reads multiple tokens and maps them into a dictionary - this is the core of the Whisper automatic speech recognition (ASR) model from OpenAI. The model can also be made multivariate by increasing the input dimension of the encoder and output dimension of the decoder. This sort of "universality" is also how multimodal LLMs work and it is my view paradigm of transformer backbones with different encoders/decoders is likely to remain fruitful in the near future.

As any in-vogue method, transformers for time-series are not without a counter-movement (rightly) questioning the effectiveness and strength of baselines used. Discussing this is decidedly a non-goal of this post and we try to stick to implementation details. Nonetheless, the context provided by an evaluation setup is valuable to properly define the problem we are trying to solve. For this reason, we begin by implementing a very simple model for time series forecasting based on a multilayer perceptron (MLP) block which will act as our baseline.

Organization: We introduce the weather dataset we use, implement a simple MLP forecasting model and train it, describe the basics of transformers, show the full model and lastly discuss multi-token decoding for longer forecasts.

Dataset

We will use a standard weather dataset in CSV form available from Kaggle, the first 5 rows of which can be seen below.

| Formatted Date | Summary | Precip Type | Temperature (C) | Apparent Temperature (C) | Humidity | Wind Speed (km/h) | Wind Bearing (degrees) | Visibility (km) | Loud Cover | Pressure (millibars) | Daily Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-04-01 00:00:00.000 +0200 | Partly Cloudy | rain | 9.472222 | 7.388889 | 0.89 | 14.1197 | 251.0 | 15.8263 | 0.0 | 1015.13 | Partly cloudy throughout the day. |

| 2006-04-01 01:00:00.000 +0200 | Partly Cloudy | rain | 9.355556 | 7.227778 | 0.86 | 14.2646 | 259.0 | 15.8263 | 0.0 | 1015.63 | Partly cloudy throughout the day. |

| 2006-04-01 02:00:00.000 +0200 | Mostly Cloudy | rain | 9.377778 | 9.377778 | 0.89 | 3.9284 | 204.0 | 14.9569 | 0.0 | 1015.94 | Partly cloudy throughout the day. |

| 2006-04-01 03:00:00.000 +0200 | Partly Cloudy | rain | 8.288889 | 5.944444 | 0.83 | 14.1036 | 269.0 | 15.8263 | 0.0 | 1016.41 | Partly cloudy throughout the day. |

| 2006-04-01 04:00:00.000 +0200 | Mostly Cloudy | rain | 8.755556 | 6.977778 | 0.83 | 11.0446 | 259.0 | 15.8263 | 0.0 | 1016.51 | Partly cloudy throughout the day. |

From it we see that we have readings for a few weather parameters with a one hour interval. In the interest of simplicity, we restrict ourselves to just the temperature for now which is in the column with index 3. We can write a PyTorch Dataset for this as follows.

class WeatherDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self):

self.frame = pd.read_csv('data.csv')

def __len__(self):

return len(self.frame)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

data = self.frame.iloc[idx, 3]

return torch.tensor(data, dtype=torch.float32)

With the weather dataset abstracted away, we can write another dataset for the actual prediction task. It should be able to do a few key things:

- Indicate

train/testsplit, separated by an appropriate buffer zone. - Get a

seriestensor of lengthcontext_lenwhich should be the input to the model, and atargettensor of lengthoutput_lenwhich is the desired output which we will use for the loss function.

We choose for the test set to start after 80% of the data points and a buffer of twice the context_len to prevent data leakage.

class TimeSeriesDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, points_ds, context_len, output_len, split="train"):

full_length = len(points_ds)

test_start = math.floor(full_length * 0.8)

train_stop = test_start - context_len * 2

if split == "train":

train_len = train_stop

self.points = [points_ds[i] for i in range(train_len)]

else:

self.points = [points_ds[i] for i in range(test_start, full_length)]

self.points = torch.stack(self.points)

self.context_len = context_len

self.output_len = output_len

def __len__(self):

return len(self.points) - self.context_len - self.output_len

def __getitem__(self, idx):

series = self.points[idx : idx + self.context_len]

target = self.points[

idx + self.context_len : idx + self.context_len + self.output_len

]

return series, target

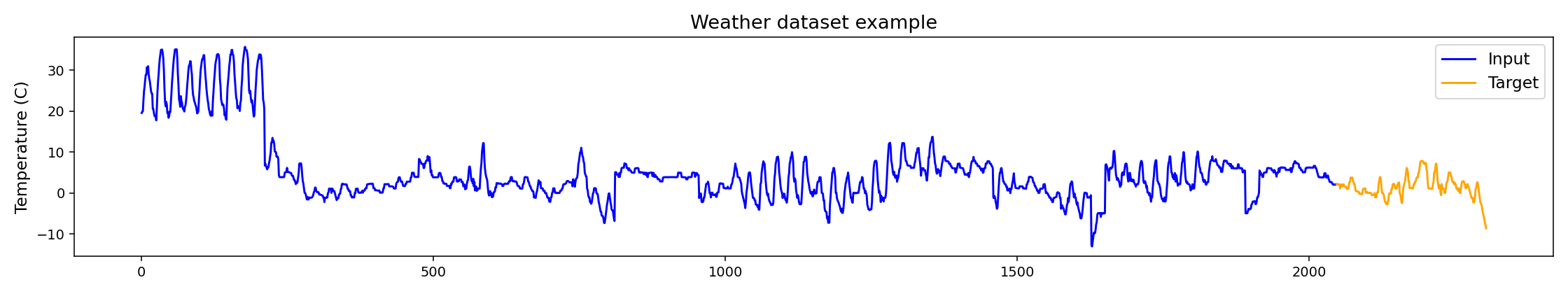

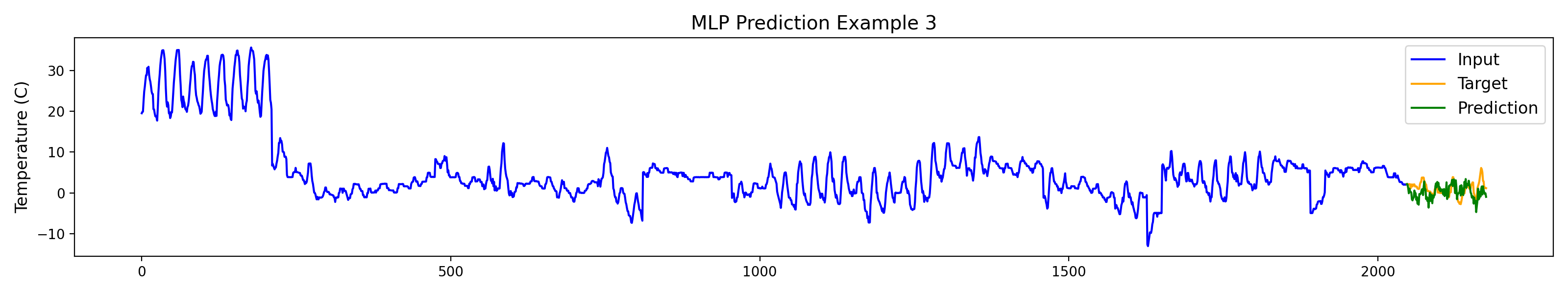

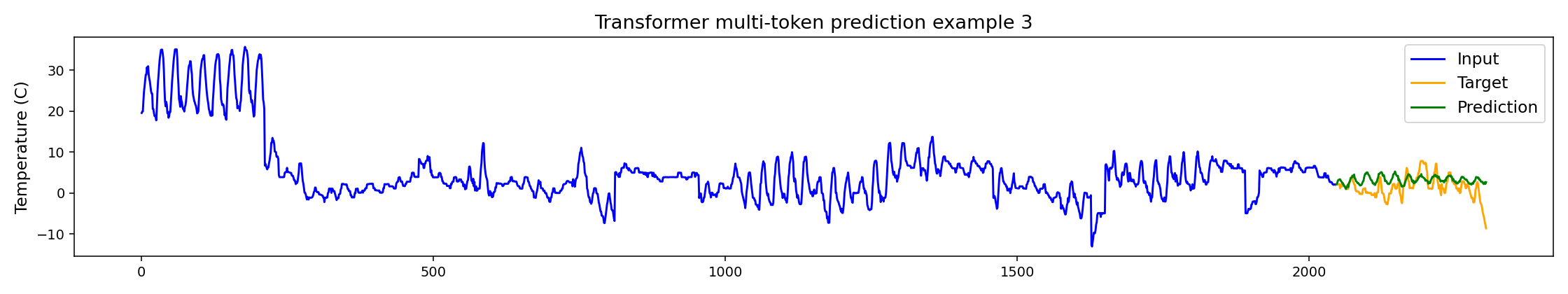

Below is an example with context_len = 2048 and output_len = 128.

The 2048 + 128 = 2176 datapoints correspond to 90 days so the high frequency details are the day/night cycle and the lower frequency energy is likely small scale weather trends. Note in particular the flatter segments and the highly irregular nature of the signal which makes it hard for a human to make good guesses other than the regular day/night cycle. We will return to this example later with predictions for comparison.

MLP baseline and model generalities

Now we turn to developing the simple multilayer-perceptron model for the baseline. Our input data, the temperatures from the table, is not dimensionless and can significantly drift over time. For this reason it is beneficial to normalize each slice we let the model act on and then invert the normalization after the model has acted. To this end, we set up the following helper functions which take an input xof shape (batch_size, len):

def normalize(x, m = None, s = None):

if m is None or s is None:

m = x.mean(dim=1)

s = x.std(dim=1)

return (x - m) / s, m, s

def un_normalize(x, m, s):

return (x * s) + m

The reason we allow the mean and standard deviations to be given as arguments is that we want future data to be normalized using the statistics from the context window. We use this in our loss function which - on account of this normalization - is scale invariant. As a basis we use the standard Mean Squared Error (MSE) \(\ell^2\)-loss function.

def normalized_mse(series, pred, target):

_, m, s = normalize(series)

pred, _, _ = normalize(pred, m, s)

target, _, _ = normalize(target, m, s)

return nn.MSELoss()(pred, target)

We can now set up the baseline model with a single hidden layer and a simple ReLU nonlinearity:

class MLPForecast(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, context_len, output_len):

super().__init__()

hidden_dim = output_len * 4

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(context_len, hidden_dim)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, output_len)

self.relu = nn.ReLU()

def forward(self, x):

x, m, s = normalize(x)

x = self.fc1(x)

x = self.relu(x)

x = self.fc2(x)

x = un_normalize(x, m, s)

return x

This is basically all that is needed for this simple model. Below is the training code which is standard with dynamic device selection and the schedulefree.AdamWScheduleFree optimizer from Meta.

if __name__ == '__main__':

output_len = 128

context_len = 2048

learning_rate = 3e-4

batch_size = 16

max_epochs = 1

device = 'cpu'

if torch.cuda.is_available():

device = 'cuda'

elif torch.backends.mps.is_available():

device = 'mps'

weather_ds = WeatherDataset()

ds_train = TimeSeriesDataset(weather_ds, context_len, output_len, split = 'train')

ds_test = TimeSeriesDataset(weather_ds, context_len, output_len, split = 'test')

dl_train = DataLoader(ds_train, batch_size = batch_size, shuffle = True)

dl_test = DataLoader(ds_test, batch_size = batch_size, shuffle = True)

model = MLPForecast(context_len, output_len)

optimizer = schedulefree.AdamWScheduleFree(model.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

model = model.to(device)

losses = []

for epoch in range(max_epochs):

print("--------Epoch {}--------".format(epoch + 1))

train(model, device, optimizer, dl_train)

test(model, device, optimizer, dl_test)

print("Training completed")

The train() and test() functions with some tqdm and plotting niceties are defined as follows:

def train(model, device, optimizer, dataloader):

model.train()

optimizer.train()

progress_bar = tqdm(dataloader, desc="Training", leave=True)

cum_loss = 0

for step, (series, target) in enumerate(progress_bar):

optimizer.zero_grad()

series = series.to(device)

target = target.to(device)

pred = model(series).squeeze()

loss = normalized_mse(series, pred, target)

losses.append(loss.item())

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

cum_loss += loss.item()

progress_bar.set_postfix(running_loss = cum_loss/(step + 1))

def test(model, device, optimizer, dataloader):

model.eval()

optimizer.eval()

progress_bar = tqdm(dataloader, desc="Validating", leave=True)

cum_loss = 0

with torch.no_grad():

for step, (series, target) in enumerate(progress_bar):

series = series.to(device)

target = target.to(device)

pred = model(series).squeeze()

loss = normalized_mse(series, pred, target)

cum_loss += loss.item()

progress_bar.set_postfix(running_loss = cum_loss/(step + 1))

print("Validation MSE: {}".format(cum_loss/len(dataloader)))

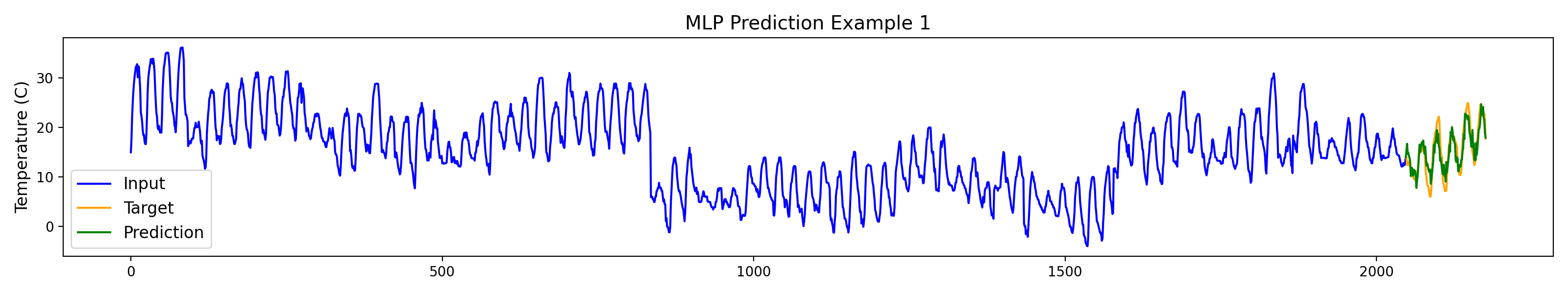

This model has 1,114,752 parameters and trains to a test MSE = 0.729 in 7s on an RTX 3070. We try it out on some examples from the test set below.

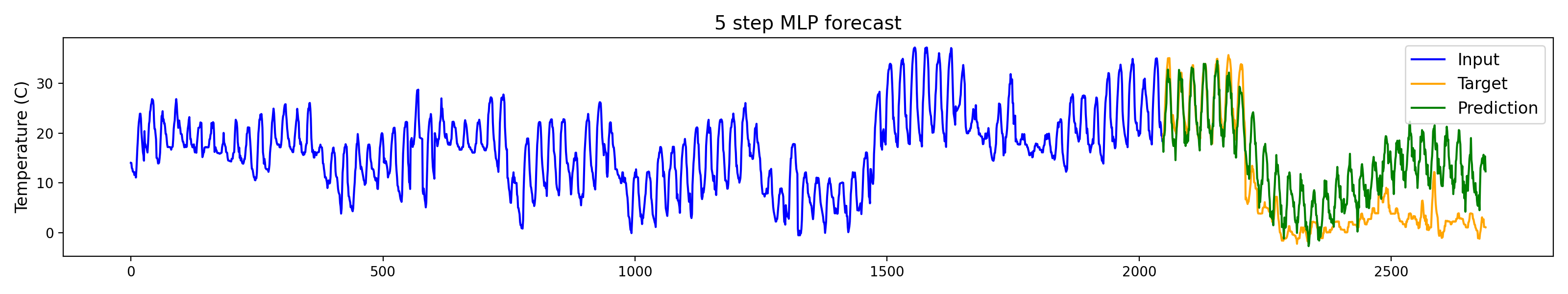

Should we wish for longer forecasts we essentially have 2 options; increase output_len or run the model autoregressively. The first of these options increases the model's parameters while the second comes at the cost of inference time. Below is an example of the autoregressive solution.

With this simpler model in place, we turn our attention to how transformers can be used to process time series data. We will return to the question of increased output_len later on.

Transformers

While the transformer architecture was originally intended for NLP applications, it is nowadays seen more as a general compute engine to which we can attach our own encoders and decoders. There are endless variations on this "general compute engine" with different attention implementations, extra steps applied to Q, K, V projections and data moved in between transformer blocks. We will treat the inner transformer block as a black box to some degree and focus on mapping to and from it.

Transformer blocks as we commonly know them are a self-map acting on a collection of context_len vectors of dimension d_model. As all neural networks, they work on batches so really it is tensors of shape (batch_size, max_tokens, d_model) which are mapped to new tensors of the same shape. Our goal will be to encode our times series of shape (batch_size, context_len) into a tensor of this form, allow a series of transformer blocks to act on it, and then decode the result into a tensor of shape (batch_size, output_len).

In NLP applications, words are split into tokens ("tokenization" -> ["token", "ization"]), each token is one-hot encoded and there is a learned embedding matrix which maps each token to a vector of dimension d_model. We could do the same for time series data by binning to map e.g. the interval \((0.1, 0.2)\) to a one-hot vector and then embed that. This approach ignores the inherent continuity of time series data, both in input and output due to the binning procedure. Moreover, it produces in the same number of tokens as input data points which can become prohibitively expensive due to the quadratic time complexity of self-attention. For image applications, the vision transformer (ViT) pioneered the idea of "patching" where the image is split into non-overlapping patches, each of which is mapped to a d_model vector through some MLP-like procedure. This is the approach we will use to encode our time series. Specifically, we will split our time series into patches patches, each of length patch_len so that patches * patch_len = context_len. In the TimesFM paper, this is done using a residual block.

class ResidualBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_dim, output_dim, hidden_dim, dropout = 0.1, apply_ln = True):

super().__init__()

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, output_dim)

self.residual = nn.Linear(input_dim, output_dim, bias=False)

self.gelu = nn.GELU(approximate='tanh')

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout)

self.apply_ln = apply_ln

self.layer_norm = nn.LayerNorm(output_dim)

def forward(self, x):

residual = self.residual(x)

x = self.fc1(x)

x = self.gelu(x)

x = self.fc2(x)

x = self.dropout(x)

x = x + residual

if self.apply_ln:

x = self.layer_norm(x)

return x

Note that we cannot use a skip connection because input_dim ≠ output_dim as these are dependent on the model dimensions and patch_length respectively.

Now we can use the encoder to go from a (batch_size, context_len) to a (batch_size, patches, patch_len) tensor by splitting up the input into vectors of length patch_len which are mapped to vectors of length d_model.

def encode_patches(self, x, patches, patch_len, encoder):

x = x.view(x.shape[0], patches, patch_len)

encoded_patches = []

for i in range(patches):

patch_data = x[:, i, :].flatten(start_dim=1)

encoded_patch = encoder(patch_data)

encoded_patches.append(encoded_patch)

return encoded_patches

By calling this function with encoder a ResidualBlock we move from a sequence of time series to a sequence of tokens amenable to transformer blocks. Before putting this representation through the transformer blocks, we need to add positional embeddings as the model otherwise is permutation invariant.

class SinusoidalPositionalEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_positions, d_model):

super(SinusoidalPositionalEmbedding, self).__init__()

self.num_positions = num_positions

self.d_model = d_model

self.register_buffer("pos_embedding", self.create_positional_embedding())

def create_positional_embedding(self):

position = torch.arange(0, self.num_positions).unsqueeze(1)

div = torch.exp(

torch.arange(0, self.d_model, 2) * -(math.log(10000.0) / self.d_model)

)

pos_embedding = torch.zeros(self.num_positions, self.d_model)

pos_embedding[:, 0::2] = torch.sin(position * div)

pos_embedding[:, 1::2] = torch.cos(position * div)

return pos_embedding.unsqueeze(0)

def forward(self):

return self.pos_embedding

For us, num_positions will be patches = context_len // patch_len unless we add some additional tokens. The output of this goes into a series of decoder transformer blocks and is then decoded using another ResidualBlock with no layer normalization or dropout. These components, and the positional embeddings, are set up as follows.

self.patch_decoder = ResidualBlock(

input_dim=d_model,

output_dim=output_patch_len,

hidden_dim=d_model,

dropout=0,

apply_ln=False,

)

self.pos_embedding = SinusoidalPositionalEmbedding(self.tokens, d_model)

self.transformer_layers = nn.ModuleList(

[

nn.TransformerEncoderLayer(

d_model,

num_heads,

dim_feedforward=d_model * 4,

dropout=dropout,

batch_first=True,

)

for _ in range(num_layers)

]

)

With this we are essentially done! Below is the full code for the model where we explicitly force the model to a decoder-only mode with causal attention using an upper triangular attention mask. Using the nn.TransformerEncoderLayer means that we only apply self-attention and no cross attention.

class TimeSeriesTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

context_len,

patch_len,

output_patch_len,

output_len,

d_model,

num_heads,

num_layers,

dropout,

):

super().__init__()

self.output_patch_len = output_patch_len

self.patch_len = patch_len

self.patches = context_len // patch_len

self.patch_encoder = ResidualBlock(

input_dim=patch_len,

output_dim=d_model,

hidden_dim=d_model,

dropout=dropout,

apply_ln=True,

)

self.patch_decoder = ResidualBlock(

input_dim=d_model,

output_dim=output_patch_len,

hidden_dim=d_model,

dropout=0,

apply_ln=False,

)

self.pos_embedding = SinusoidalPositionalEmbedding(self.tokens, d_model)

self.transformer_layers = nn.ModuleList(

[

nn.TransformerEncoderLayer(

d_model,

num_heads,

dim_feedforward=d_model * 4,

dropout=dropout,

batch_first=True,

)

for _ in range(num_layers)

]

)

self.register_buffer("tgt_mask", self.causal_mask(self.tokens))

def encode_patches(self, x, patches, patch_len, encoder):

x = x.view(x.shape[0], patches, patch_len)

encoded_patches = []

for i in range(patches):

patch_data = x[:, i, :].flatten(start_dim=1)

encoded_patch = encoder(patch_data)

encoded_patches.append(encoded_patch)

return encoded_patches

def forward(self, x):

x, m, s = normalize(x)

encoded_patches = self.encode_patches(

x, self.patches, self.patch_len, self.patch_encoder

)

x = torch.stack(encoded_patches, dim=1)

x = torch.cat((x, self.output_tokens.repeat(x.shape[0], 1, 1)), dim=1)

x = x + self.pos_embedding()

for layer in self.transformer_layers:

x = layer(x, src_mask=self.tgt_mask, is_causal=True)

x = x[:, -1, :]

x = self.patch_decoder(x)

x = un_normalize(x, m, s)

return x

def causal_mask(self, sz):

mask = torch.triu(torch.ones(sz, sz) * float("-inf"), diagonal=1)

return mask

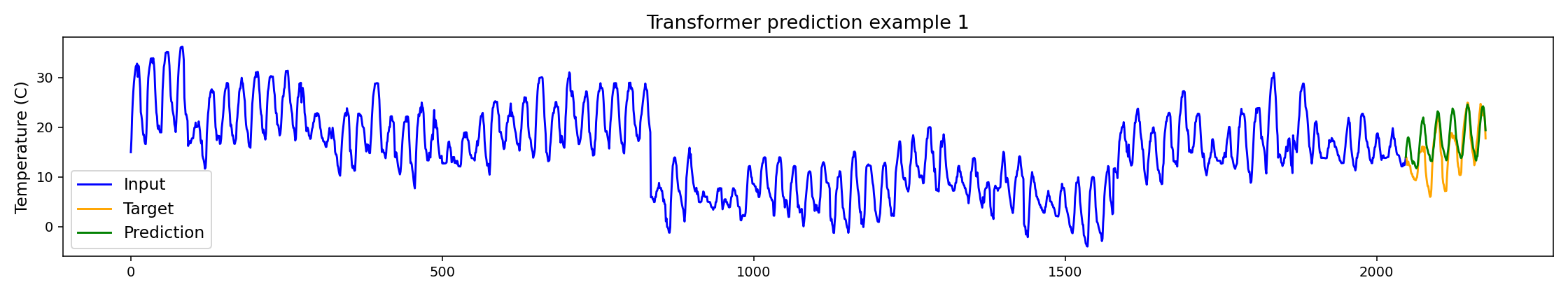

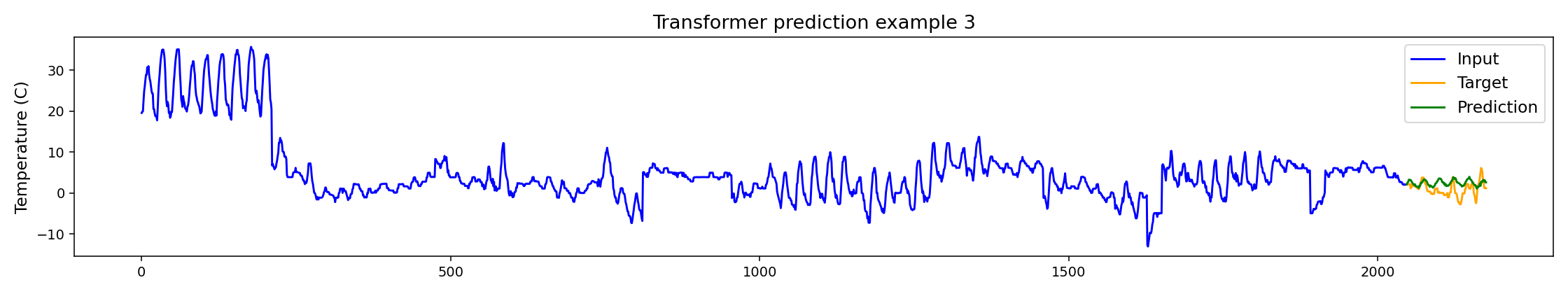

With the hyperparameters patch_len = 32, d_model = 256, num_heads = 4, num_layers = 2, dropout = 0.1, this model has 1,794,176 parameters and trains to a test MSE = 0.445 in less than a minute. This is considerably better than the MLP baseline and we see this also in the examples.

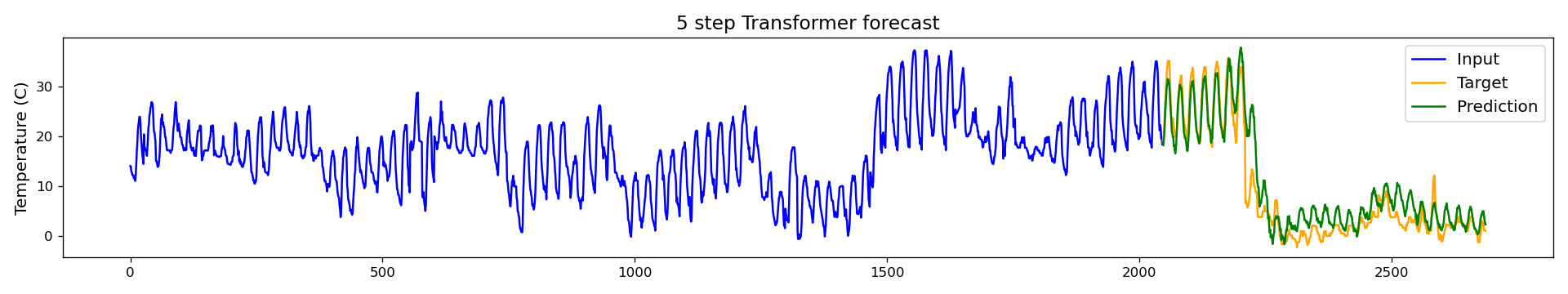

For longer forecasts, we can again use autoregressive decoding which yields slightly better results than in the MLP baseline case.

Naively increasing output_patch_len here would put a lot of work into the decoder residual block. In the next section we will look at decoding several tokens into sequential output patches.

Multi-token decoding

Lastly we will look at two options for increasing the output length of our model(s) beyond the autoregressive approach; increasing output_len and decoding multiple tokens. The former is very straight forward but for multi-token decoding we will need to use something like the encode_patches() function instead of just x = self.patch_decoder(x[:, -1, :]). Our decode_patches() function will be as follows.

def decode_patches(self, x, output_patches, output_patch_len, decoder):

decoded_patches = []

for i in range(1, output_patches + 1):

decoded_patches.append(decoder(x[:, -i, :]))

return torch.cat(decoded_patches, dim=1)

In addition, we also add output_patches = output_len // output_patch_len tokens to the end of the transformer sequence so that the model has appropriate room to work on the prediction tokens. This is analogous to the [CLS] token in a BERT-style transformer.

def __init__(...):

...

self.output_tokens = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(1, self.output_patches, d_model))

...

def forward(...):

...

x = torch.stack(encoded_patches, dim=1)

x = torch.cat((x, self.output_tokens.repeat(x.shape[0], 1, 1)), dim=1)

...

An alternative to this, employed by the Informer model, is to split the transformer backbone into an encoder which acts on the history and a decoder which is padded with empty tokens - a minor change from our approach.

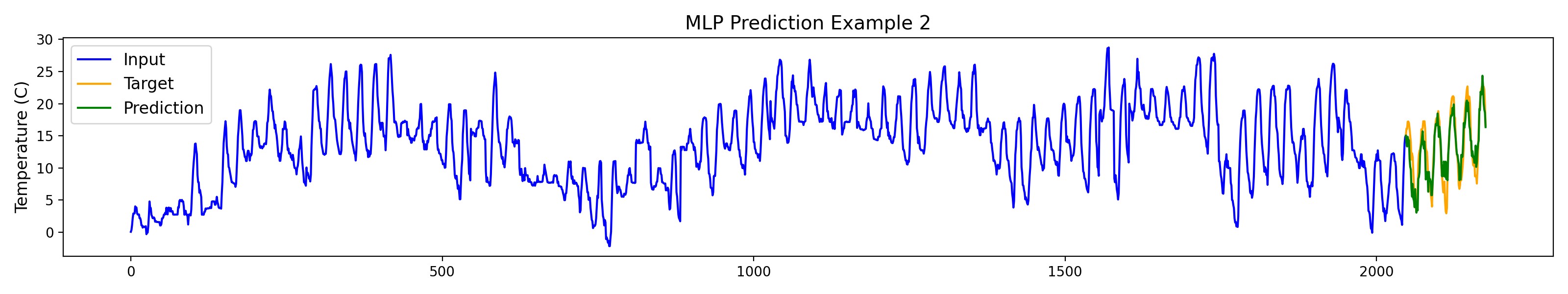

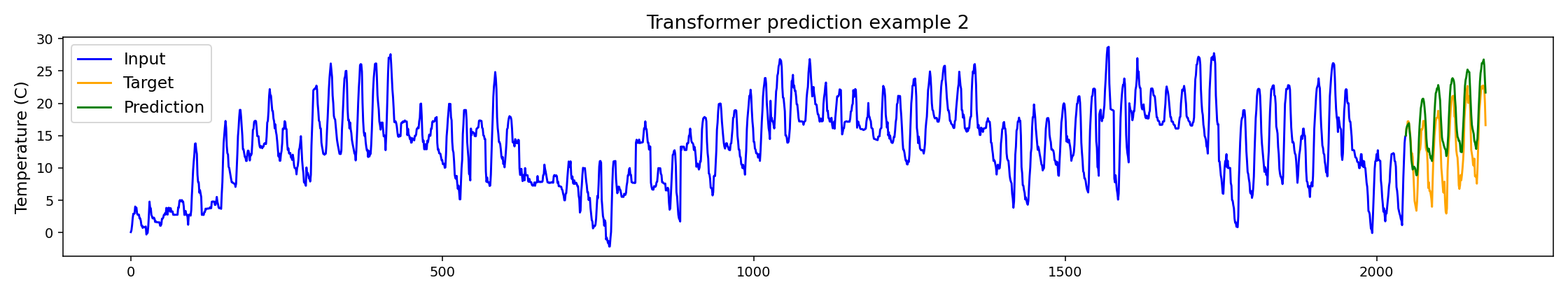

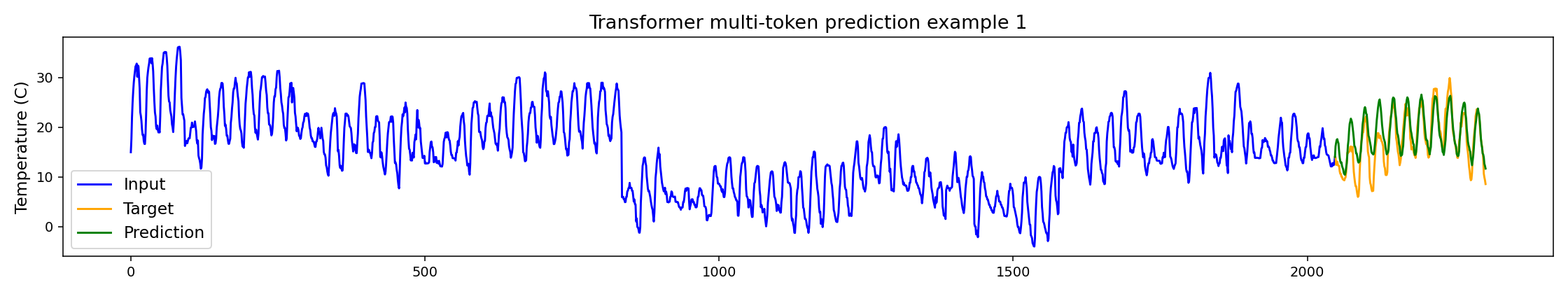

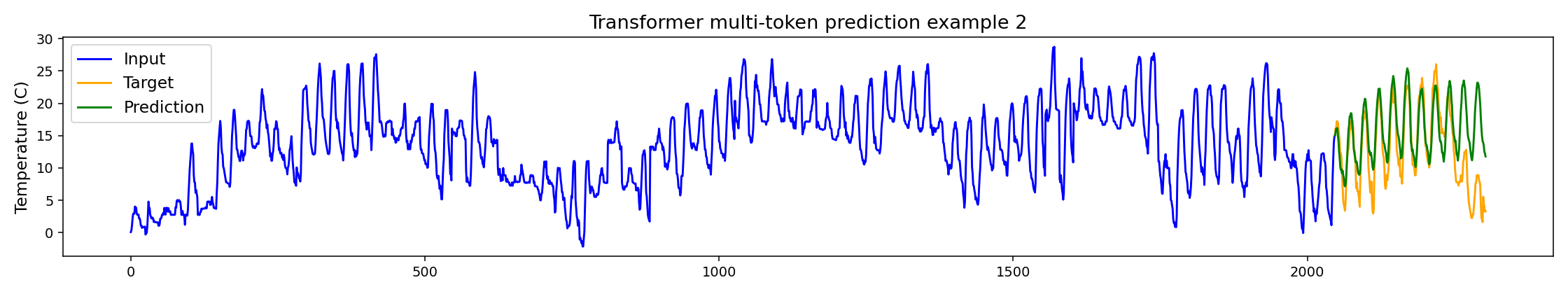

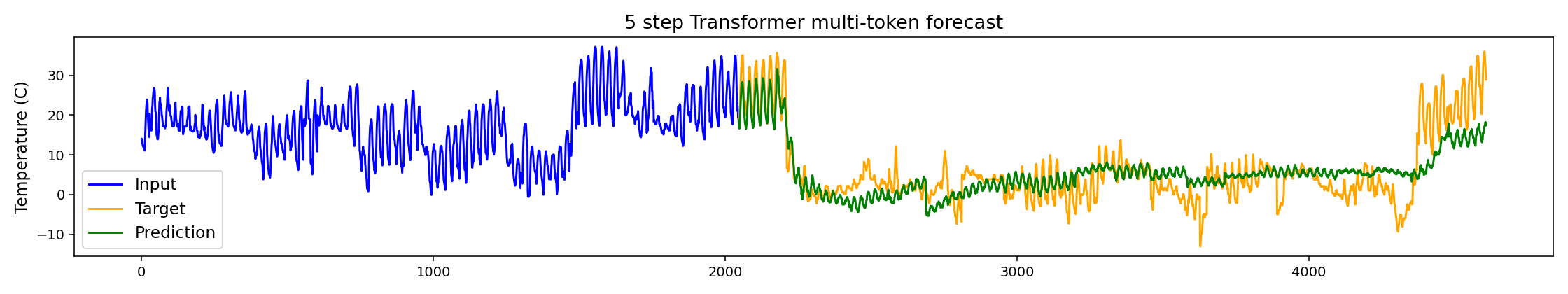

Below are examples for output_tokens = 4.

The increased output length likely promotes reducing the oscillation frequency of the predictions since we use the mean square error which punishes errors superlinearly. Of course, we can run the multi-token model autoregressively to get even further forecasts.

At this point, the predictive power of the forecast drops to basically zero as we are trying to predict the hour-wise temperature almost three months in advance. Obviously this type of model is better suited for a time series with denser sampling.

We've now gone through most of the model and evaluated it. As mentioned in the introduction, the full TimesFM model has some additional features. Most notable is probably the support for variable input length which is only useful for a model which is meant to be reused in different contexts. Hopefully, you the reader are better prepared to implement/understand/use other related time series models.